No Room

On charity, spectacle, and the quiet work of actually showing up

The Parking Lot

It was the Friday before Christmas, and I was circling the parking lot of a very large church in Buckhead, Atlanta. And when I say very large, I mean (using my Master’s in English Literature vocabulary) ginormous.

“This place is insane,” I texted David. “It’s packed, and there’s not a single parking space.”

I looped the well-signed lot—"Donor Parking Only,” “Handicapped Only,” “15-minute Parking”—for the third time before spotting a man in a highlighter-yellow vest waving me down. With orange wands dramatically slicing the air, he looked like he belonged on an airport tarmac, As I pulled up beside him, my soccer-mom 4Runner might has well have been coming in for a landing.

He leaned down, peered into my window, and said, “Sorry ma’am. There’s no room here. But you’re welcome to perch under the pergola and wait for someone else to pull out.” He pointed one glowing wand toward the entrance I had already passed maybe six times at that point.

I had come prepared to feel a lot of things that morning—awkward, curious, maybe even nostalgic—but overwhelmed wasn’t one of them. And yet, there it was, rising unexpectedly in my chest as I finally pulled into a space that felt more like a privilege than a convenience.

I turned off the engine and sat for a moment, hands on the wheel, taking in the building in front of me: massive, immaculate, perfectly orchestrated, Christmas banners hanging just so.

And then, to my right, was something I hadn’t prepared myself to see.

Sheep.

Yes, sheep. Furry, fluffy, meandering sheep. In a tiny pen directly beside the sidewalk leading into the church.

I scratched my head.

The Awkard Onlooker

My bewilderment was interrupted by a text from David.

“We had to bring two cars because we bought so many gifts. My sons are ahead of me in a white SUV. I’m behind them. Ten minutes out.”

As I waited, I watched the throngs of people stream inside. Women in perfectly printed dresses, babies perched on hips or gripping the hands of toddlers in smocked outfits. Men in suits hustling from their cars toward the doors, likely slipping out of important meetings at the very last minute.

Designer bags. Cashmere sweaters. Polished shoes. Glittering jewelry.

And me—in a Tantrum sweatshirt—watching from my car.

And sheep.

I wasn’t sure what I expected as I hit I-85 that morning, but it definitely wasn’t this. I thought I was coming to a domestic violence foundation to help David unload Christmas gifts he and his family had purchased for six families in need.

My naive, sheltered, and perhaps judgmental self imagined pulling up to a run-down, lonely church. I pictured a foundation director rushing out the front doors, visibly exhausted, embracing David with a you have saved us kind of gratitude—the sort of moment that ends in hugs, relief, and the quiet satisfaction of having done something good.

Instead, I was sitting under a pergola in one of the nicest areas of Atlanta because there was no parking space for me, sweating in my Tantrum sweatshirt while beautiful people walked into church to pay their respects to our Lord and Savior before celebrating his birthday.

The Santas

Just then, two little Tanns pulled up behind me in a white SUV, shyly waving. I’d never met David’s sons, but I’d heard all about them in the five years I’d worked with their proud father. And proud he should be—they were miniature versions of him: tall in stature but humble in spirit, kind, thoughtful, with just enough edge of humor.

Moments later, David pulled in behind them, aptly wearing a green Tantrum sweatshirt and a bright red scarf. As he stepped out of the car, I did what I always do when I see David in person—I bounced toward him and jumped into his much-taller-than-me arms for a bear hug.

To his sons, I said, “Hi! I’m Lindsay. I’m your dad’s biggest fan.”

Nerd out much, lady? I could almost hear them thinking.

“Sorry I’m a little late,” David said. “I had to run by Target to buy a Nintendo Switch. I found out one of the kids loves gaming, and I thought it’d be a good way for the whole family to play together.”

The Gifts

The boys opened their trunk as David opened his, and my eyes widened. They may as well have been driving sleighs.

There were Squishmallows, baby dolls, Legos, art sets, games, soccer balls, water toys, figurines. But there were also space heaters, diapers, feminine products, and cleaning supplies alongside gift cards, candles, lotions, blankets, sweaters—all the things that make one feel human in the cold of winter.

“Damn,” was all I managed to say.

David had mentioned earlier that week that his family had been shopping for these families, but I had no idea it was this much. But then again Lindsay, check yourself. This is David Tann. Give him a task and he will give it 150 percent.

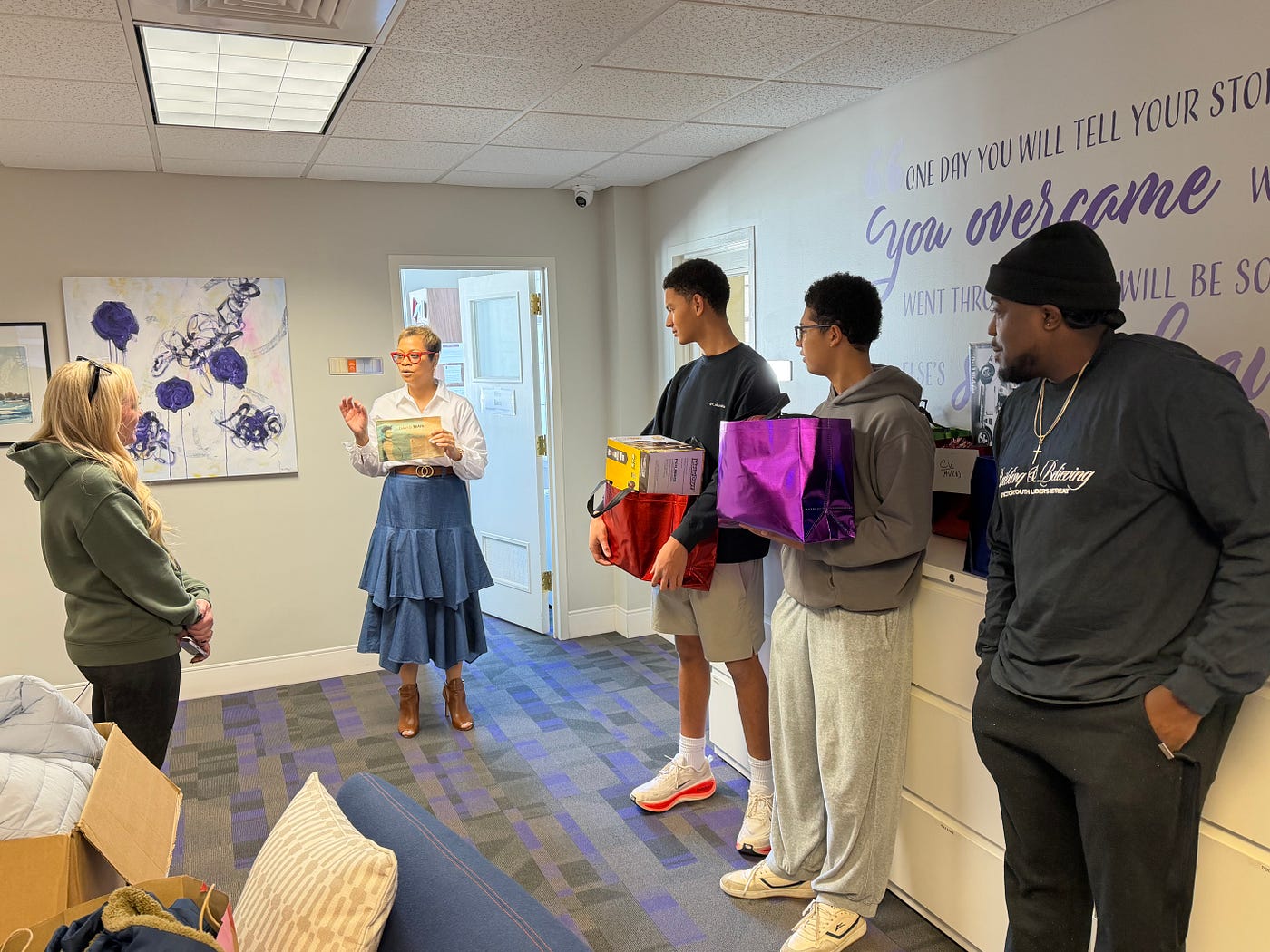

Just then, out the church doors came the foundation leader’s daughter, stylish in an oversized plaid blazer, jeans, and chestnut braids falling to her elbows. After greeting us warmly and doing a double-take at the gifts, she brought over a cart, and we began loading it—along with our arms—with presents.

For the next hour, we carried gift after gift into the foundation’s office, filling tables and spilling onto the floor. Soon the foundation’s founder joined us, as elegantly dressed as her daughter, thanking us again and again. And then, she disappeared into her office and returned holding a faded newspaper article featuring David from when he’d been nominated for a marketing award.

“When I first read this years ago,” she said, “I knew I wanted to work with David and Tantrum. And now look at how this relationship has grown.”

That’s when I realized: this wasn’t charity as I had imagined it. It was something far more mutual.

David hadn’t simply shown up during a moment of need. This foundation’s leader had supported him for years—championing his work, believing in his talent, opening doors, and inviting him into a community that mattered to her. Their relationship wasn’t transactional; it was layered. Built slowly, over time, through trust and shared commitment to the people they serve.

Standing there, surrounded by gifts, I realized this wasn’t a story of rescue. It was a story of reciprocity—of people showing up for each other in different ways, at different moments, with what they had to give.

The Juxtaposition

Still, I couldn’t shake the awareness of where we were. We were unloading gifts for families navigating domestic violence at one of the most affluent churches in Atlanta, while just outside the doors, hundreds of well-dressed families gathered for a Christmas pageant.

I realized later that the sheep—the ones that had puzzled me earlier—were there for a reason. After the service, families would pose beside them for photos: a live nativity scene experience, carefully curated and beautifully staged.

I stood there holding a box of diapers, unsettled by the closeness of it all—the reenactment and the real thing happening within steps of each other. I felt my own quiet judgment rise as I watched families move from pageant to photo op, participating in a version of goodness that felt comfortable and contained.

And then it hit me.

I hadn’t bought a single one of these gifts that we were delivering today.

David and his family were the ones who had spent weeks listening, noticing, shopping. I had simply shown up at the end to help deliver them. In my own way, I wasn’t so different from the families I had been silently critiquing, arriving for a moment and participating in something meaningful without fully carrying the weight of it.

Still, that realization didn’t make me cynical. It made me quieter.

What Showing Up Really Looks Like

The women who led the foundation were nothing like the people I had unconsciously imagined. They were poised, articulate, beautifully dressed—women who didn’t need rescuing. What they needed were resources, consistency, and partners who respected the work they were already doing.

Standing there with them, it became clear that my discomfort had never really been about wealth or appearances. It was about the stories I had carried in with me—the ones that told me what need was supposed to look like, and who was supposed to hold power in moments like these. As those stories began to loosen their grip, I felt something else open up instead: room. Not the kind you find in a parking lot, but the kind you make when you’re willing to let go of tidy narratives and sit with something truer.

When we finished unloading, the sheep were still there—patient, calm, waiting for the next family to pose beside them.

And maybe that’s the part that stays with me.

Not because the pageant was wrong. Not because the gifts were enough. But because real compassion doesn’t need staging. It doesn’t photograph well. It requires an open mind—one willing to question its own assumptions—and the self-awareness to notice when judgment is easier than engagement. It looks like consistency, humility, and the courage to stay present long after the moment has passed.

I don’t know exactly what that kind of showing up will require of me yet, but I do know it asks more than observation, more than critique, and more than arriving at the end. It asks me to participate differently—to remain curious, to do the unglamorous work, and to make room in myself for discomfort, responsibility, and growth.

About the Alma Domestic Violence Foundation: The Alma Domestic Violence Foundation (ADVF) strives to educate, empower and celebrate survivors of domestic violence while helping them to achieve financial stability, self-sufficiency and an understanding that they are never alone on their journeys.

ADVF was founded in 2005 by Alma G. Davis as a result of her own personal trials and triumphs with domestic violence. “Having received my own first set of black eyes at the tender age of 14, I felt it was only right to reach back and grab those who are pushing their way forward,” says founder Alma G. Davis.

Now a respected businesswoman and community leader, Davis has made it her passion to uplift women and teen survivors. Headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, the foundation serves thousands of victims at 64 facilities across the state. Alma is a safe haven for all — ready to save and assist in the rebuilding process to ensure victims can be survivors.

https://almadvf.org/

About the Author:

Lindsay Niedringhaus

Director of Operations, Tantrum Agency

Lindsay has 20 years of experience leading and managing marketing projects for a variety of clients in a wide range of industries including higher education, retail, hospitality, nonprofit, and B2B. Prior to Tantrum, Lindsay founded TealHaus Strategies, an award-winning marketing firm based out of Greenville, SC. She also founded HerHaus, a women’s membership organization that provides networking and educational opportunities related to wellness. Lindsay received her Bachelor’s in English from Furman University and her Master’s in English Literature from Clemson University.

.png)